Welcome back to the iServalan Music School podcast. Today I want to talk about someone whose music seems to live in the marrow of all musicians, and perhaps in the marrow of music itself: Johann Sebastian Bach.

What is it that makes him so thrilling, so endlessly compelling, so impossible to ignore? That’s what I want to explore in today’s reflection.

🎙️ Podcast Essay: “Bach, the Thrill of Order and Fire”

Ah, Bach! Even the name seems carved in oak, steady and resonant. Strong and proud. But the sound of his music? Ah, that is something else entirely. It is not oak — it is flame, it is water, it is a thousand glittering birds flying in formation and then suddenly.... breaking apart, only to return again in perfect unity like starlings flocking on Brighton Pier.

Why is Bach so thrilling? We might begin with structure. His music is precise, crystalline, every note interlocking like the stones of a cathedral. But to call it merely mathematical is to miss the point. For within that order lies a kind of turbulence — a tension that sets the heart racing.

Take a fugue. On the surface, it is an exercise in logic: one voice enters, then another, then another, each weaving around the others with impeccable discipline. But listen closer — it is theatre! It is drama! Each voice seems to pursue the other, chasing and teasing, like actors on a stage, like children at play. And in this chase, you feel the thrill of inevitability: it all must come together, it will come together, but the route is unpredictable, dazzling.

When I place my bow to the cello for the Suites, I feel it immediately. The opening Prelude of the First Suite — simple, flowing arpeggios — feels like a kind hand extended. Yet even there, in the apparent simplicity, is the thrill of momentum. You cannot stop once it begins; the current carries you, and by the end you are drenched in something vast, something both intimate and cosmic.

And then there is the sense of breath. Bach’s lines breathe. They inhale, they exhale, they arch like the ribcage itself. For all the talk of counterpoint and structure, what moves us most is that the music feels alive. His notes seem to remember that we are embodied creatures — we breathe, we walk, we dance, we pray — and he gives us music that does all of these things at once.

What astonishes me is how democratic his thrill is. A child can delight in Bach without ever naming a cadence. A scholar can spend a lifetime chasing his patterns. A harpsichordist finds a universe in the Well-Tempered Clavier. A violinist stands at the cliff edge of the Chaconne, staring into eternity. And we, mere mortals at the kitchen table with the radio on, are lifted just the same.

Perhaps that is why he endures. Bach does not offer beauty only to the elect, only to the educated. He gives it freely. He is thrilling because he manages what so few artists can: he makes logic feel like passion, and he makes passion feel inevitable.

I think sometimes about the sheer audacity of it. To write so much, and yet so much of it so good. To weave order and fire together in such balance that centuries later we still cannot unpick the threads. And when we play him — on cello, on piano, on organ, even on synthesizer — we are reminded that within us, too, lies this duality: the desire for order, the longing for freedom. Bach gives us both. We are spoilt indeed.

So yes, we can say, Bach is wonderful. But perhaps it is truer to say: Bach is thrilling because he gives us ourselves — magnified, clarified, transfigured. He takes the heartbeat, the laughter, the tear, and spins them into something infinite.

And that is why, after all these centuries, we still return. Not out of duty. Not out of habit. But because, when the bow touches string, or the fingers touch keys, we feel alive again. The thrill. The fire in the order.

Until next time, may the counterpoint of your days carry both order and flame.

#bach #readings #sarniapodcast #iservalanmusicschool

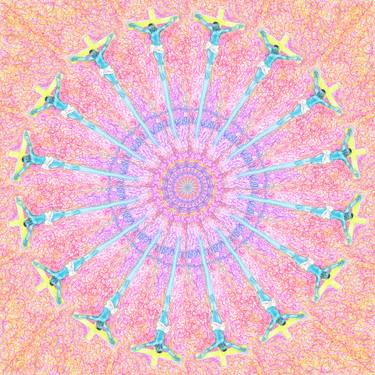

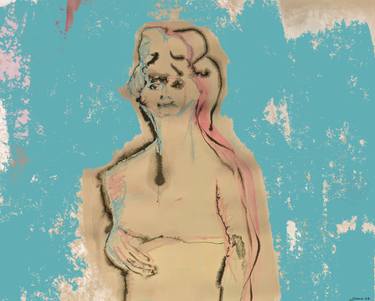

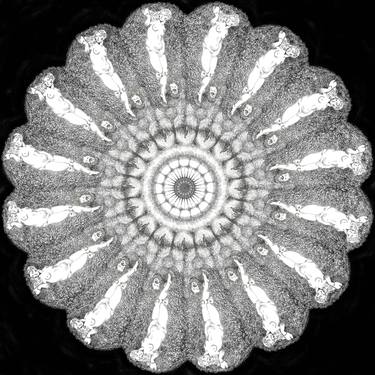

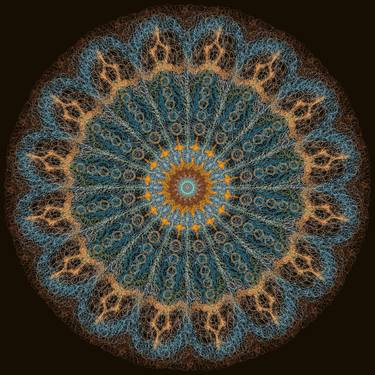

Artworks by Sarnia de la Maré FRSA

Prints From $100

$1,685

Digital on Canvas

36 x 36 in

$2,210

Digital on Paper

36 x 38 in

Prints From $120

Prints From $100

Prints From $100

$1,340

Digital on Paper

20 x 33 in

Prints From $100

Prints From $100

Prints From $100

Prints From $100

$1,055

Digital on Paper

36 x 36 in

$10,590

Digital on Paper

25 x 25 in

$8,490

Digital on Paper

25 x 25 in

$1,665

Digital on Paper

25 x 25 in

Prints From $40